| I am not an advocate of a return

to painting, nor an agent of post modernism, but part

of a generation of modernists aware of a heritage, a

child of ruins and catastrophe. François Rouan |

|

Françios Rouan is the type of painter that I had always

hoped would be at work in France today. With so much of the

great painting of our modern epoch having come out of French

culture, its language and its way of thinking it seemed natural

to assume that there must exsist a painter with an eye on the

implications of such a heritage. However during the eighties

when the market and the institutions of the art world were trumpeting

the return of painting, Rouan was strangely passed over and

a younger generation of artists such as Garouste and Blais stole

the international limelight as French representatives of the

zeitgeist of the time. In retrospect perhaps Rouan was lucky

to have escaped the ‘hype’. Although what he still

lacks in international reputation is amply made up for by his

standing within France. Many would go so far as to say Rouan

is France’s most important living artist.

Rouan is an artist who manages to square a circle with a mind

that is responsive to the extreme intensities of French thought

whilst engaging with painting at its most physical level. He

follows a path that many French artists have trodden. It is

easily forgotten that Matisse’s progress as one of the

most radical sensualists came out of a complex and sometimes

painful intellectual inquiry. In the three decades that comprise

Rouan’s work there is not only an impressive body of painting

but there is also evidence of a rich web of discourse that ranges

from the political to the sociological and the psycho-analytic.

Such a relationship to ideas and theory in the visual arts is

usually seen as the preserve of a more conceptual practice.

Rouan’s early years as an artist coincided with the turbulent

time of the sixties. Politics were important to him and events

like the Algerian war led him to align his support with the

Maoists. Yet painting never became a crude support for agitprop

or socially significant practice. He cast his net wider than

that with an understanding of the radical political nature of

constructivism and the Bauhaus as instruments of an ideal society

which seemed within reach. In France around 1968, left-wing

and predominately Marxist thought was providing the tools to

evolve conceptual models of society within which practitioners

such as artists could exercise complex yet strategic positions.

An example could be found in the writings of the Situationalist

Guy Debord who was even then prophesising the emergence of global

capitalism where societies would be dependent upon spectacle

and amusement to socialize its members into the emerging opiate

of consumerism. It would seem that Rouan at this time responded

to such ideas by focusing upon painting’s complex relationship

with human scale and the body. His reference though would shadow

the ever fragmentary nature of the representation of the human

body in a modernist history of painting. Rouan has never engaged

in holistic mirror like representation relying on the false

comfort of a suspect and nostalgic humanism. Rouan’s painting

depicts the body in fragments, as imprints or as traces.

From 1971 until 1978 Rouan went to Rome and painted at the Villa

Medicis which is the French equivalent of the British School

in Rome. Balthus was the director of the Villa and an unlikely

yet warm relationship built up between the two painters. Unlikely

because Rouan’s work at the time was uncomprimisely abstract

and somber and bore no obvious affinities to the much senior

artist. Les Portes, his first major series of works were made

in Rome. They have become known also as “tressages”

because of the technique employed where strips of canvas are

literally woven together. These works relied on subtle plays

of elements appearing and disappearing, upon repetitions and

the sense of how the smallest element is incorporated into a

larger dimension. These seemingly abstract works relied upon

the viewer encountering them in an emphatic way. These doors

could not be breached if viewed from a perspective that painting

was merely an inverse realm of a world of pure transparency.

Moreover Rouan has even spoken of how photographing these works

was impossible.

It was les Portes that first brought Rouan into contact with

Jaques Lacan. He had heard about the problems of photographing

them and asked to see them. He ended up acquiring some drawings

and a relationship evolved between the painter and the psychoanalyst.

What attracted Lacan to Rouan’s work is open to much speculation

but Rouan has located the ideas of Lacan’s that interested

him. It was the concept of a void which seemed to be the link

between the two men. Rouan has pinpointed Lacan’s notion

“when one approaches the central void which is most interior

to the subject and which we call jouissance, the body tears

itself to bits” as being of particular interest to him.

Rouan echoes this concept himself when he says “Art finds

its necessity when it reaches this capacity to construct a central

void that, by means of its very invisibility, manages to indicate

the blind spot that is at the center of our thirst for beauty.”

From this vantage point Rouan could examine the modernist epoch

not merely as a history of formal developments where the engine

of ‘originality’ would push toward an increasingly

fragmentary representation of the world and the human body.

Such fragmentation could more readily be seen as an aspect of

consciousness which concerns truth about the status of the pictorial

object rather than just a story of formal innovation. Rouan’s

present exhibition Jardins Taboués at the Musée

Villeneuve d’Ascq near Lille includes a series of paintings

which are meditations derived from two Picasso nudes from 1908

and 1909, one of which is from the museum collection. Picasso

in the first decade of this century pushed the figure toward

a faceted and stark dismemberment under the influence of African

art. The votive power of Picasso’s images of that period

challenged the devotion painting to the particularity of appearances.

These images mark the departure of painting from pure visuality

into a darker possibly more primal, visceral world. Rouan’s

return to such motifs in the spirit of a copyist is a type of

credo and recalls many other French painters who have staked

their colours to artists of the past as way of moving forward.

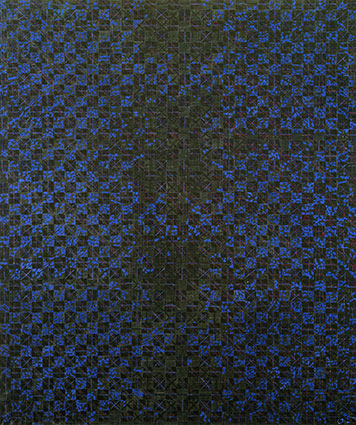

The exhibition at Villeneuve d’Ascq concentrates on paintings

from the early eighties until the present. His paintings generically

known as Stücke from around 1988 move like a mood swing

toward a series known as the Coquilles which are still in progress.

The word Stücke comes from “Shoah” the film

about the Holocaust where an eyewitness described the corpses

as “stücke”, as inanimate pieces. These paintings

are caught within the dynamic of cubist collage and the obscene

systematic mass destruction of human beings in this century.

Like Keifer who juxtaposed the ambiguity of Wagnerian motifs

with the realities of German history Rouan seeks a rhyme and

even an ethical discussion between geometric dismemberment and

the horror of industrialized genocide.

The atmosphere of the Coquilles strike a different note. Here

actual imprints from bodies are made onto canvas in a way that

echoes Yves Klien. This relationship of the imprint of the body

dates back to a series of paintings made in the early nineties

entitled The Taboo Garden. The reference is toward desire and

the tabooed zones of the body which are the focus of the imprinted

flesh. However another echo is detectable in the Coquilles which

opens up another area of discussion about this aspect of Rouan’s

production.

The Genius of Venice exhibition held at the Royal Academy, London

in 1984 was notable because of the effect one painting had upon

a generation of artists. It was Titian’s great Flaying

of Marsyas which was then not widely known. Its effect was spell

binding. I was a student at the time and visited the painting

many times. On each occasion I’d find myself amongst a

huddle of spectators many of whom I recognized as other artists.

Rouan also visited the exhibition and he too witnessed the gruesome

sight of the upside-down Satyr being skinned for losing the

musical contest with Apollo. The stripping away of the dark

dionysiac skin by the powers of Apollianian measure and rationality

struck Rouan as deeply as many others who saw that painting.

It has been said that Titian’s image is in essence a breakthrough

in a transition between a classic to a modern age. This is perhaps

so and it is thus no coincidence that the aged Titain replaced

a mirror like and transparent articulation of space for a more

opaque surface metered by somber tactile values and uncompromising

marks of the brush.

In the Coquilles (literally translated as shells) Rouan prints

his own body onto a surface which is submerged in a opacity

of marks. In this process Rouan flays his own body. His skin

becomes the membrane for a transfer technique which is essentially

monoprinting. The density of the surface and the effect of the

body marks creates a multiplicity of readings. Exteriority and

interiority are equal possibilities in these pictures. They

allude to the border condition that painting can so succinctly

inhabit. The equation of positive marks and negative body traces

cancel themselves out so that the picture becomes a type of

void which as I have described before is at the core of Rouan’s

thinking. The corporal negative imprints are of the tabooed

parts of the body which have become rejected and repressed into

an other and that have taken a shroud of concealment. Rouan

does not seek to merely reveal that which is normally concealed

within something we choose to call an unconscious. His gambit

is more a type of hide-and-seek where a quality pops out only

to disappear into another schema. The Coquilles in this sense

relate directly to the Tressages. The binary game of weaving

strips of canvas into a greater fabric was also a type of hide

and seek where as much of the painting remains concealed as

revealed. The cancellation or abscences within this duality

suggest the importance of such a discussion of a psychic void.

The other will always remain un-namable. The other will always

be displaced by rationalistic systems and remain in shadowland.

All that can be hoped for is an intimation of what is at the

heart of our condition. A painting can become a place for an

encounter with what will always remain a suggestion, an intimation

of what is essentially an absence or a lacking. Rouan, as always,

amply articulates this;

“Art finds its necessity when it reaches this capacity

to construct a central void that, by means of its very invisibility,

manages to indicate the blind spot that is at the centre of

our thirst for beauty. Dizzying notions that are not given to

our experience in the large movable mirror that we call psyche,

but in the very picture where the circulation of the soul between

life and death leaves its mark, as though in wax - persona -

in the breaches where light and shadow split.”

It seems that Rouan is treading a path which curiously links

him to an artist like Gerhard Richter. With Richter there is

also an awareness that painting inhabits a curious position,

that it has become embroiled into an aesthetic of negation due

in part (in the case of Richter) to its relationship with photography

which took over from painting in the domain of mirror representation

thrusting it into the relative instability of abstract, non-mimetic

practices. Richter incorporates the endless sense of a switching

between the polarities of painterly potentials into his regime.

Polarities that move between expression and construction; mimesis

and rationality. Rouan inhabits a similar territory except the

readings of his work differ. Lacan is significant to Rouan whereas

Adorno’s writings can be used to form the backdrop of

a critical discussion around Richter’s work. What is important

to recognize with these artists is that any discussion about

a ‘return to painting’ is not simply a widening

of a pluralist context in a type of cultural free-for-all. Another

type of awareness is possible. We are locked into a reality

where abstraction is not merely the assertion of crass libertine

values and figuration is not simply the deployment of dubious

ideas of tradition and high art. The truth bound up within this

antique activity is maybe not so positive; it is a white cane

enabling us to probe a ‘blind spot’ that lays at

the heart of us.

Mick Finch, 1995.

|